The World Karate Organisation Shinkyokushinkai has announced the dates for the 12th world open karate tournament next year, to be held on November 9th and 10th. This year will see a venue change to the Musashinomori Sports Plaza, as the organisation’s traditional venue, the Tokyo Taiikukan, undergoes renovations ahead of the 2020 Olympic games.

This tournament is the equivalent of the Olympic games for our organisation, and the pinnacle for all competitors involved. With under 14 months of preparation time remaining, each athlete needs to evaluate where they stand in their training process and formulate a plan to address those aspects of their preparation most critical to success. Proper planning is one factor that separates top fighters from the very elite.

The construction of an annual training plan begins with an analysis of the athlete’s current physiological status, based off of a detailed testing battery. This testing battery should include assessments of mobility, strength, power, and metabolic capacity, and should be performed in conjunction with an assessment of recent competition performance, to identify priorities in terms of training time allocation. The annual plan should also take into account the timing of competitions, as this will dictate the amount of training time dedicated towards specific aspects.

The training year (which we refer to as the macrocycle), should be broken into 2-3 cycles of different phases of training. These include the preparatory, competition and transition phases. Within these phases, specific mesocycles (or blocks) of training should be used to target specific qualities of performance that need to be addressed. Although each block will focus on one or two different qualities, maintenance work for other qualities should also be implemented to prevent regression. For example, a higher-volume hypertrophy phase should still contain a baseline amount of higher-velocity power work to maintain this quality.

Preparatory Phase

The preparatory phase should be separated further into general preparatory and specific preparatory.

The General Preparatory Phase (GPP) should be higher in training volume and lower in training intensity. The higher volume is used to build a training base for the later stages of training when intensity is increased. This may include building an aerobic base, or a muscular endurance base, given the specific needs of the athlete. When combining training modalities (resistance training and energy systems (“cardio”) training), higher repetition resistance work should be combined with slightly lower intensity aerobic system (as opposed to higher intensity glycolytic work) as this has been shown to cause less training interference between the competing modalities1.

This phase will generally tend to be shorter in more advanced athletes, as they often already have a strong training base, and longer in lesser experience athletes, or those returning from injury and/or a longer lay-off.

Due to the high volume of training during this phase, a decrease in certain areas of performance, particularly in technique, will be observed1. This period of training is not a time where perfection in technique in terms of speed, reaction, and accuracy should be a primary focus.

As an athlete moves into the Specific Preparatory Phase (SPP), the exercises should become more specific in nature, and we define this specificity base on the muscular patterning of the exercise, the speed of execution, and direction of movement2. Along with an increase in training intensity comes a concomitant decrease in volume.

Concurrent (performing both resistance and energy systems training) should be altered to target more anaerobic system development (shown to be less interference) in combination with higher-intensity, lower volume strength/power work, again due to the decreased interference effect3.

Competition Phase

The competitive phase may also be sub-divided into pre-competition and competition.

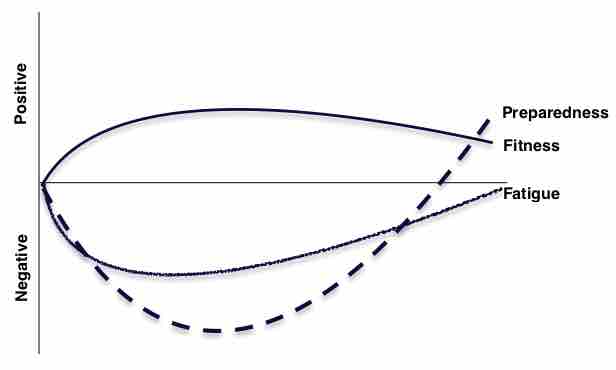

The goal of the pre-competition phase is optimise preparedness by decreasing fatigue. When we have high volumes of training our fitness levels are high, however our fatigue levels are also high leading to a decrease in preparedness. Using intelligent changes in programming, are can dissipate the fatigue at a faster rate than the reduction in fitness, and therefore maximise our performance potential.

In an attempt to decrease resistance training volume, the exercises used should increase in their specificity to the task, and should prioritise higher-velocity movements. Energy systems work should also be specific to the demands of the event, both in terms of duration and intensity, as well as modality (mitts/pads/bag as opposed to non-specific modalities). Technical and tactical work should also be emphasised during this period.

The Competition phase in team sports refers to the “in-season” period, where games are played on a regular basis. In combat sports this refers to the weeks leading up to the event, and in the last 2 weeks will involve some type of pre-event taper. Training volume should be further reduced, with a small amount of resistance training used as maintenance. Technical and tactical training should be highly specific to the competition demands, as well as the specific opponent(s) to be encountered in the event.

As a combat athlete should ideally only peak for competition 2-3 times during a calendar year, in instances where there are more than 3 competitions, events should be grouped together and treated as 1 competition phase. The figure below depicts how this would look for a athlete with 4 events over the year.

Transition Phase

The transition phase allows recovery from the event preparation and the event itself, and should include some variation in activity, even performing completely different sports. However, the mistake many athletes make is taking too long off before commencing the next preparation phase. The volume of training will have already been reduced significantly during the pre-competition and competition phases, and in order for the system to be able to tolerated the volume of the next GPP, the training load must be built back up as soon as the athlete is ready.

The transition phase is also an important time for reflection on the past training cycle and the event, re-testing of important variables, and planning for the next training cycle.

As with anything in life, failing to plan = planning to fail. Having a basic understanding of periodisation concepts allows us to put a plan in place to optimise the sequencing, and subsequent effectiveness of our training interventions.

This is just a quick snippet of the through process behind planning the training process. A thorough discussion of periodisation and training planning is featured in The Science of Striking, due for release in early November. Email us to receive notification of its release!