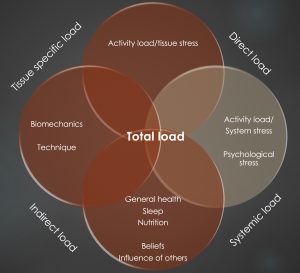

The last two posts discussed tissue-specific load. This post will discuss direct systemic load, and we will break this into physiological and psychological.

PHYSIOLOGICAL

We’ve discussed previously how training load can cause overuse in the injured tissue and lead to pain. However, a rapid increase in overall training load may also lead to injury in an area not specifically related to increased load. Let’s say for example an athlete is 8 weeks out from a fight, and they introduce swimming 3 times per week to their S&C program as additional energy systems work. Following this they develop lower back pain after deadlift as part of their strength program (an exercise that they usually don’t have problems with). Even though the low back-specific load has remained consistent, the increase in the overall training load has decreased that athlete’s tolerance to back-specific load and subsequently led to injury. This is why it is important to monitor and manage total training loads. This is also why it is important following injury to maintain training loads where possible, so that once the injury settles, there isn’t a dramatic spike in load. If a back injury makes it difficult for an athlete to deadlift, run and grapple, they may have to switch to swimming, other pain-free hip strengthening exercises, and intelligently increase their volume of striking work to keep up the chronic workload.

PSYCHOLOGICAL

If a fighter experiences an increase in their psychological stress levels, this in itself is a type of load that can contribute to injury. Stress causes changes in the endocrine system (in particular increased cortisol production), as well as the functioning of the brain and central nervous system, all of which can dramatically influence the perception of pain. If our subjective assessment indicates that a change in stress or anxiety was the biggest change in an athletes load prior to the onset of injury, then stress management techniques should play a major part in the rehabilitation process. If an athlete is prone to extreme stress levels at certain times in their fight preparation, coaches may need to consider lowering training loads at these times.